''I like media companies as a business,'' Mr. Buffett said. ''I'm interested in the product. I always thought the media had a bright future, but it took Wall Street a long time to appreciate that.''

Buffett liked the media industry. He invested in The Washington Post, turning an initial investment of around $10M into $1 Billion 25 years later – a 100-fold return. In addition, Buffett has been a long-term fanboy of Tom Murphy and Capital Cities, speaking about them regularly at annual meetings.

However, tucked away in the corner of their 1970s annual reports, are a couple of advertising agency investments that ended up being home runs.

The Industry: late 1960s

The advertising agency stocks were "high fliers" in the late 1960s, according to the New York Times. They were essentially royalty businesses on the advertising expenditures of customers, capitalising on three major trends:

Clients (such as CPG or oil companies) expanding globally.

Clients outsourcing advertising. E.g. It was better for Mars Inc to focus on making and selling candy bars rather than developing advertising campaigns in Australia.

Large global agencies developing a business model out of acquiring small agencies – i.e. an advertising holding company.

Ken Auletta's Frenemies talks about the start of the Agency Hold Co:

“The pioneer who launched the “holding company” era was Marion Harper, Jr., president of McCann-Erickson, who acquired a number of agencies and by 1960 had placed them all under a new umbrella, the Interpublic Group. Advertising agencies began to go public, and attracted famed investor Warren Buffett, who in the 1960s took sizable positions in McCann-Erickson and Ogilvy & Mather. “You know the best business to be in?” Kenneth Roman, former chairman of Ogilvy said, recounting Buffett’s words. “It’s one where you’re shaving in the morning and can look in the mirror and say, ‘Today, I’m going to raise prices.’ And you can do it.”* As was true in most giant industries, the belief that size conferred advantages was rampant. Size conferred more leverage to raise prices and lower costs, provided a bigger global footprint to pitch clients anywhere, enabled synergies that offered efficiencies, and boosted profits by applying cost-cutting pressure on newly acquired assets to improve the parent company’s margins.”

So this became the game.

As clients expanded their global footprint, large ad agencies were able to offer a "one-stop-shop", offering services across the world and one client point of contact. The large agencies then bought up small agencies in every geography when they discovered one that had major client relationships or expertise that could become competition.

For large clients, this was amazing, as they only needed one vendor relationship and a guarantee of quality – e.g. if Chevron got marketing support in the US and Kazakhstan through a single agency, it was worth it, rather than spending their own time on it. And most importantly, if the Marketing Director of Chevron only had to make one phone call to manage its media relationships, reducing hassle. And as we know:

Reducing corporate hassle was (and still is) a mega business!

The big agencies got bigger as a result, and the smaller ones either got crushed or bought up. This created valuation disparity between large and small agencies – making the acquisition of small agencies by large ones a viable business model. Here's what Buffett had to say on the topic in Money Masters*:

“There are few big international agencies, and there will be fewer new ones, since it’s getting harder and harder to break into the club. At this point a J. Walter Thompson controls so much business that it can just buy an agency in a new territory that becomes interesting, such as Brazil or the Middle East. A smaller agency would have trouble making a competitive offer.”

Another driver of the valuation gap between small and large agencies was that large agencies could institutionalise IP, processes, creative, and client relationships – whereas small agencies had too much value tied to the founder. If the founder walked away, the clients and value would disappear with him. Whereas at a larger agency, while CEOs were often charismatic and likely to be missed, they’d probably be replaced without much fuss with no major interruption to the company.

Side Note - There are many parallels between the old advertising business and the modern enterprise software game. Large companies don't want to have to deal with 100 vendors who they pay anywhere from $2,000 to $100M. They'd rather deal with just one Microsoft or Salesforce, that is able to offer a large suite of products globally. On the other hand, large companies would not even pick up a phone call from a company selling them $2,000 of software. It's a win for the small software provider to be bundled into the distribution network of Microsoft or Salesforce.

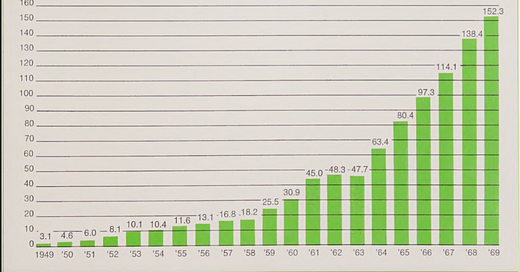

Again, the business model of reducing corporate hassle is timeless.Back to ads… The business was so lucrative that here's what Ogilvy & Mather billings from the New York office looked like over time:

Operating Profits followed suit and showed a similar trajectory. These businesses looked unstoppable.

The advertising agencies wedged themselves between the advertiser and the media, becoming a broker of advertising space with no costs apart from people. Warren Buffett again explains the attractiveness of the space in Money Masters:

“The perfect business is a royalty on the sales of a major company, as distinct from its net profits. One example is the big international advertising agencies, which net 1% or so after-tax on their client’s advertising expenditures, and often 5% or so on their own revenues. The clients, not the agencies, invest the capital to build those sales.”

Agencies (not only advertising ones) remain great businesses to this day. The only caveat being the need to act swiftly and cut headcount when revenue slows down.

A business slowdown was not conceivable in the late 1960s, however!

This era was about growth, prosperity, and investment banks selling the prospects of Agency Hold Cos to raise capital from inflated IPOs. The valuation gap between small and large agencies became even larger - with the influx of cheap IPO capital going to the large agencies.

Side note: The current market for SME software roll-up businesses (e.g. Constellation Software and friends) looks similar to the ad agency business in the 1960’s. The model is similar - to raise cheap capital from public markets and then use it to buy small software companies for 3-6x EBITDA. The model is great while the multiple arbitrage works…Some notable agencies we know today went public around this time:

Ogilvy and Mather - 1967

J Walter Thompson - 1969

Interpublic Group - 1971

Yes, these were the go-go years that inspired the TV show Mad Men. Growth was everywhere. And there was plenty of money to be made. Suits with suspenders, B.S., cigars and whiskey everywhere!

The business model was great - but vulnerable to a recession in a big way. When clients got into financial hardship, the first expense to go was advertising.

Why? It was hard to turn off an oil rig, or shut down a factory producing chocolate bars, just because of a temporary downturn. Trying to cut overheads was no easier - job cuts have serious impact upon the lives of workers, and company morale. But advertising - this could be cut without hurting employees or taking big risks (at least in the short term). Of course there would be job cuts at the ad agency – but these were someone else’s problem! NIMBY to the rescue!

As we move towards the 1970s, we see that that is exactly what happened.

The 1970s

This decade had a totally different economic backdrop for corporate profits. The post-war boom ended harshly and productivity no longer increased in a straight line. Double digit inflation turned into stagflation, which ultimately turned into recession in 1973-4.

Corporate profits decreased, ultimately crushing client budgets destined for advertising spending.

Side note - In fact, we saw a repeat of this in 2022, some 50 years later. When company profits fell, advertising spending got cut, and MAG7 companies with advertising business models went from rapid to zero growth. It's not that these businesses automatically became shitcos - it's more that the marginal trader/investor panicked at scale. Astute investors could have picked up Meta shares for $90, which subsequently zoomed up to $510 within a year once they adjusted their headcount and cost structure.The 1973/4 period was panic on steroids - with real reasons to be scared:

American manufacturing saw the first threats from foreign competition.

The OPEC Oil Embargo of 1973 caused an energy crunch in the West, leaving it vulnerable to the whims of frenemy states.

High interest rates put a damper on consumer spending relative to the 1960s.

Agency stocks (in fact most stocks) reacted to the bad economic prognosis, getting dumped wholesale - even though agencies themselves had not stopped growing.

This NY Times article has a few snippets which showed criticisms of the advertising agencies at the time:

There are a number of reasons for this lower‐than‐average market valuation of the agency securities. As Anne McKane of Merrill Lynch Pierce Fenner & Smith asserts, their investment characteristics are “cyclical”, although she foresees “growth” over the long term.

The mercurial nature of agency‐client relationships is offen cited as a depressing ingredient affecting ad agency stocks. Yet behind the headline‐grabbing desertions of a big advertiser from a big agency, are many stable relationships.

It's true that advertising agencies were ultimately dependent upon advertising budgets of clients. Crunches in corporate profits affected agencies directly – creating some cyclicality in some industries – for example oil or automobiles. Additionally, client moves from one agency to another were big news items in the business section of newspapers. The somewhat shaky client retention profile of the business was put under a magnifying glass due to its high profile nature.

Some critics believe that most agencies are little more than a reflection of one person, Mary Wells Lawrence of Wells, Rich, Greene, for example, whose Image dominates the organization and who is seen as largely responsible for its development. Such an overview tends to lead to a downgrading of ad agency securities because of the realization that anything can happen to this individual.

Agencies were full of charismatic, Don Draper-like figures. David Ogilvy was the CEO of Ogilvy and Mather. If such key people left, was there a business remaining? Or would they take IP and clients with them?

Fears and general economic gloom resulted in the large, public agency share prices tanking, as some agencies even recorded losses in 1973/4 – confirming the fearful prognoses in the news.

On valuation - What's funny is that advertising agencies themselves were buying smaller agencies at 6-8x earnings, while their own shares were trading at 2-4x pre-tax earnings. The valuation dynamic between large and small agencies had flipped vs. the 1960s.

Warren Buffett apparently encouraged David Ogilvy to “buy more of the best agency” - and buy back his own shares to capitalise on the warped valuation dynamic.

Buffett Investment

Around the time of peak gloom, somewhere in 1973/4, Berkshire put $2.7M into Ogilvy & Mather, and $4.5M into Interpublic Group.

Buffett wasn't worried about key person risk that the headlines suggested - when it came to the large agencies. Again, from Money Masters:

“A local advertising agency is quite another matter. Buffett would not buy a share in a brain surgeon, but in the Mayo Clinic, yes, it’s become institutionalized.”

By this time the large agencies had institutionalized IP, process, client relationships and talent. They were no longer a one-man-shows.

“Interpublic and Ogilvy & Mather, two of the top five or six agencies worldwide are to him the most interesting of them as investments. In 1974 Interpublic sold at less than two times pre-tax earnings per share, and half of the market price of its tangible assets, although this unique enterprise represents a well-earned royalty on the gross income of Exxon, Carnation, Buick, and Chevrolet. Small agencies at that time were being bought at perhaps three times that price. In a way, the situation was actually better than in 1932, since by 1974 it was quite clear that the companies themselves would not fall apart.”

In retrospect it turns out the fears were overblown, and corporate profits (therefore advertising spending) started to recover by 1974. The agencies themselves aggressively bought back stock as they felt their own fortunes turn, some of them even trying to go private altogether at cheap valuations.

Behind the renewed attention to Madison Avenue's internationally‐operating Shops are surprisingly good earnings in 1975, forecasts of sharply rising advertising expenditures in 1976 and the growing power of the big agencies.

Seven of the largest 11 American agencies are publicly‐owned — and as such have had to contend with the disillusion that set in over the last few years when some of their counterparts “went private,” or bought back their own stock at depressed prices.

Among those that acquired all or most of their outstanding shares were Clinton E. Frank, McCaffrey & McCall and, just this year, the TracyLocke Company of Dallas. Wells, Rich, Greene, also tried, but unsuccessfully, to reacquire all of its shares.Never the less, the public companies enjoyed higher profits last year, even though the recession did not end until the second quarter.

From reading the newspapers of the day, it was clear that client losses were overemphasised, whereas boring long-term client partnerships were ignored. Cyclicality was deemed a real threat, whereas the stability of media buying habits of large corporations was underemphasised. And in general, media headlines accompanied stock market movements - a phenomenon well described in one of my favourite books The Halo Effect.

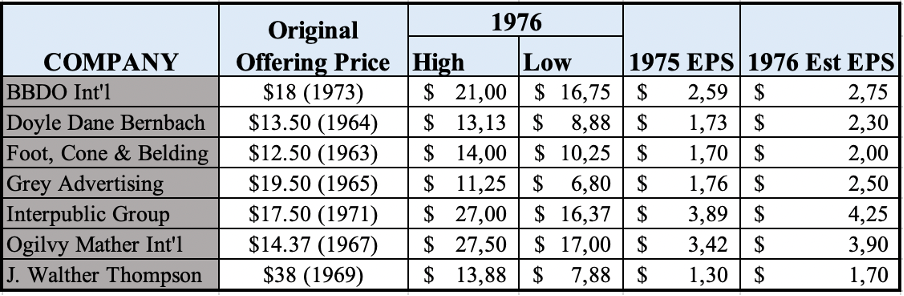

Here's the table from this NY Times Article about the earnings and valuations of the advertising agencies post 1974:

The stocks remained cheap well after 1975, all with single-digit PE multiples. Probably only a handful bought during the extreme panic of 1973/4 - and probably only a few had liquid net worth to do so at the time.

Buffett wasn't done buying after 1974 it seems. He committed $1M more to Ogilvy and Mather in 1978 according to the tables in his annual letters, well after the trough of the bear market. He wasn't a sniper at the bottom after all, but the stocks got so cheap that he didn't need to be.

How did the business go on to do?

Buffett's selling of the agency stocks began around 1982. IPG (Interpublic) had gone up roughly 9x in value, and Ogilvy around 6x by the time he completely exited.

Not a bad annualised return – 25% and 19% respectively - given that he held these stocks for less than 10 years.

Is there anything we can take away from this investment – apart from the usual “Buffett is the GOAT”?

The toughest part of any investment business is to build a structure that spits out cash, and also have a funding cost advantage.

In Buffett’s case that was the insurance operation which started to come to life after the National Indemnity purchase in 1967.

The Nebraska regulator was also more chill than other insurance regulators, allowing higher percentages of capital to be invested in equities. Buffett’s insurance operation combined with a relaxed regulator allowed for the flexibility to invest in equities at the right moment.

The profitable insurance business also allowed for a negative real cost of funding over time.

Buffett was also rather disciplined on valuation. He’s famous for winding down the Buffett partnership in 1969 when other investment managers were rising to stardom from bubble-riding.

The structure of Berkshire, combined with Buffett’s temperament allowed him to take advantage of the advertising agency stocks trading at 2-3x pre-tax earnings. After all, without the structure and temperament, one wouldn’t have been holding cash at the bottom tick in 1973.

Though most of us can’t emulate Buffett’s temperament, we can emulate the structure to some extent. Having a regular income and investing the proceeds is preferable to a fund structure with client redemptions and inflows at exactly the wrong time.

But now let’s back to our story…

What would have happened had Buffett held these two stocks?

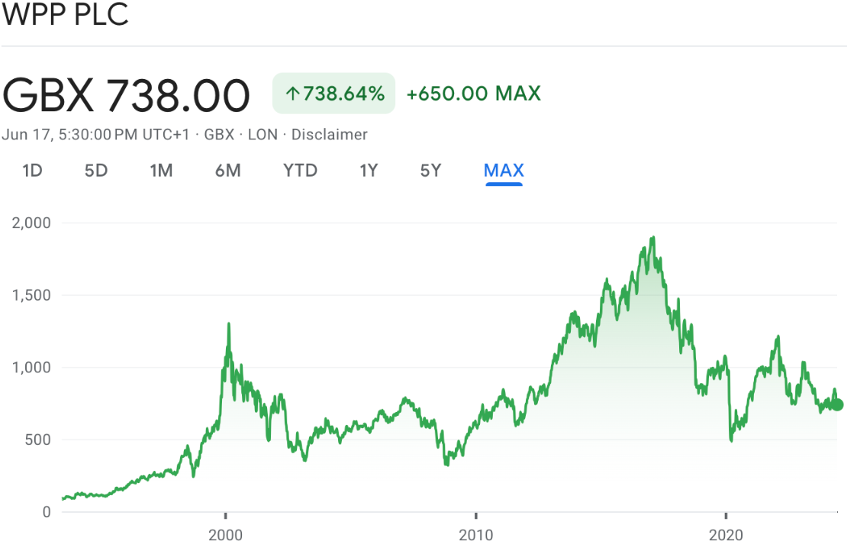

WPP bought out Ogilvy & Mather in 1989 for $864M - which was by far a premium to where Buffett sold shares. The stock chart itself doesn't reach all the way back to Buffett's sale of Ogilvy shares, but we could infer that he would have made another 10 times his money had he held. Making the Ogilvy investment at least a 60x. Probably more.

IPG is a clearer story, and conveniently, the Google Finance chart reaches all the way back to 1985, where Buffett originally sold. From there to now, IPG did 16 times. Simply holding the shares from then to now would have given Buffett a return of around 150 times - and more if he had sold during the Dot Com Bubble.

It's clear that these were great businesses, and remained surprisingly great for a long time. They managed to reinvent themselves through the TV era. The transition to online was tougher. Though agencies adapted, they still weren't unscathed by the internet gatekeepers Google and Facebook.

Through the ups and downs, Berkshire kept watching the industry.

Berkshire's 2012 WPP offer

WPP is the holding company that purchased Buffett's favourite agency Ogilvy & Mather in 1989. The CEO of WPP, Martin Sorrell, was a controversial but charismatic leader, who often pissed people off.

In 2012, he wrote an op-ed in the Financial Times addressing criticisms of WPP's compensation policy (which by today's standards look tame!). It turned out to resonate with Warren Buffett, who called Sorrell and made an offer for WPP:

The former WPP boss recalled the circumstances behind Buffett's approach: "There was a rumpus about [my] compensation. Warren had read an op-ed that I’d written in the _FT_ and called and said, ‘I think WPP should be a part of Berkshire.’

Talks fell apart on price, where Buffett didn't move up to the 30% premium over market price demanded by Sorrell.

"We had a brief conversation. He’s very shrewd. He’s very fixed and cuts to the quick. He’s very fixed in terms of pricing and the premium he offered was not sufficient – the premium was about 15%, maybe a little bit more.

"The premium for a UK listed company was 30% and we couldn’t persuade him to go to that.

"I would have loved to have done that if it had been at the right premium. The offer was 925p. Our share price was about 825p."

I found it interesting that Buffett continued to follow WPP for decades after he sold a subsidiary's shares. Quite amazing when you think of the focus and discipline to wait patiently for the right price again before making a move.

And as we can see from the WPP chart above - the deal would have been OK overall - but not a home run, as we’ll explore below…

How has the advertising model evolved since the 2000's?

Stratechery was critical of the “one-stop-shop” ad agency model in the era of Google and Facebook. Brands went online directly with Google and Facebook with the help of user-friendly advertiser onboarding. This created two dynamics:

1) Big brands like Kraft Heinz or Pampers didn’t play for a long time.

This gave room for internet-native brands to rise and steal share off traditional FMCG. Since they could advertise directly online, they didn’t need advertising agencies to support their media placements. Dollar Shave Club was a good example of this, stealing share from Gillette before being acquired by Unilever for $1B in 2016.

2) The advertising holding companies were late to the party, too slow to build or acquire online expertise.

Digital agencies formed to help reach consumers online and took the lion share of the agency profit pool online.

Agency hold cos were shut off from the internet at inception. They have since caught up – but too little, too late. They acquired digital agencies and expertise too expensively and too late to catch the wave at the perfect point. It shows in the share price: WPP and IPG haven’t returned to their pre-2000 market cap.

Agency hold cos are nowhere near as invincible as they were in the 70s. They were gatekeepers of all important media - a position they can’t claim to have online. However, they are still capital-light they are still good businesses. Dividends and repurchases alone can get shareholders to an OK place. And though they might not be relevant in the future, milking large corporate clients is still a very lucrative business until then.

What’s Next for the Advertising Agency Business?

The ad agency business scrambles with every technology change. Generative AI is yet another example for the business of content creation. Adobe Firefly launched in 2023, and since then brands such as Coca Cola and IBM have used it to do things like generate and localize content such as ad campaigns, product labelling, images, and text – work that was formerly handled by profitable digital agencies. On a smaller level, Agency Hold Cos can’t keep up with the smaller content creators on Tik Tok, IG etc. Additionally, smaller agencies themselves may not want to sell to Agency Hold Cos and be “integrated”. And if they do want to sell, there is far more competition from technology investors who can very often add more value at the cap table than Agency Hold Cos.

So where’s the value add?

It’s hard to see Agency Hold Cos disappearing entirely in the short run. Television, newspapers, outdoor, and certain amounts of online media are still intermediated by them. But it’s questionable as to whether they can make the next technology and media platform jumps on time to stay ahead of the smaller, nimbler competition who have alternative sources of capital.

In summary, I’d just reiterate three things:

The capital cost advantage of Agency Hold Cos vs. smaller agencies is getting weaker.

The Agency Hold Cos might struggle to adapt to future technology and platform shifts on time.

Their core business with traditional media and corporate clients is still very lucrative.

However, if you were asking me today - I wouldn’t bet on an Agency Hold Co, vs. just starting a small agency myself.