Investment Breakdown - NVIDIA and Mellanox

There are so many different kinds of great investments - not just the “GOAT fund manager bought and held a 50x” type stuff.

I find corporate investments interesting - in particular technology investments in fast-moving industries. Some common themes I’ve found:

Short half-life of investment - i.e. the technologies they acquire may be irrelevant soon - but still worth acquiring.

Deterrence - many technology investments are made to deter competition or make them irrelevant.

Standard setting - when it’s clear that a technology might become a standard, it’s necessary to acquire it at all costs.

Often these investments are tactical - and are made on a company’s way to finding a defensible business model, rather than being standalone great decisions.

NVIDIA’s acquisition of Mellanox displays all three somewhat - so is a great case study for high tech investments.

Enjoy and make sure you subscribe! I’ll scour the business landscape to break down more investments

NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang wears leather jackets and speaks in hyperbole about high performance computing. He has been the hero of the nerd community for decades.

NVIDIA has also lately been a stock market hero. The 5-year chart alone shows a 30-fold increase in share price - a 96% CAGR. Graduate employees 10 years ago turned into deca-millionaires - if they held on!

It’s therefore clear why “NVIDIA is just Taylor Swift for dudes".

But let’s go through a short history of NVIDIA before we jump to 2019 and set the scene for the Mellanox acquisition.

1993 - 2019 - A Short History of Nearly Everything NVIDIA

Founding

NVIDIA was founded by Jensen Huang, Chris Malachowsky, and Curtis Priem in 1993 at Denny’s - where they somehow agreed to start a high performance computing company.

They were talented engineers - Jensen having most recently worked at LSI Logic. In fact, when it became clear that he was going to quit LSI Logic, Jensen was so well regarded that the founder of LSI himself personally recommended Jensen to Don Valentine of Sequoia Capital.

“Don, I’m going to send a kid over.”

Apparently Jensen botched the pitch to Don Valentine, but his reputation at LSI saved him. Don handed over the money and said:

“If you lose my money, I’ll kill you.”

This Acquired Podcast goes into great detail of the history of NVIDIA and is super entertaining. Jensen Huang is a great story teller.

Zero Billion Markets 🎮🎮

One of Jensen Huang’s key philosophies repeated through the years is the insistence on “zero billion dollar markets”.

His idea and experience came from a mix of common sense, and NVIDIA’s history of seeing ahead and entering spaces that didn’t really exist.

An example: NVIDIA entry into gaming in the 1990s. Gaming was an industry where nerds were goofing around. It was not yet a serious market and garnered zero respect from serious investors or corporations.

Yet that’s exactly where NVIDIA chose to play, developing graphics cards for the gaming industry.

"Because one of the things you can definitely guarantee is where there are no customers, there are also no competitors."

What gaming was though, was a use-case for the latest graphics chips, demanding huge performance and technology breakthroughs to get better gameplay and visualisation. NVIDIA catered to this market, and in the process, built itself a temporary competitive advantage.

However, as Jensen said, NVIDIA was always:

“30 days from going out of business.”

In high technology this was generally always the case. But in NVIDIA’s case, they survived several near-death experiences. The Acquired series on NVIDIA can take you through each one in detail - but for our purposes today, it will suffice to say that near-death experiences formed NVIDIA’s culture of resisting complacency.

CUDA and AI

One of these breakthroughs was CUDA - which stood for “Compute Unified Device Architecture”. Originally, NVIDIA GPUs were not programmable, and could only be used out of the box with default settings. NVIDIA, however, noticed that users began to hack the GPUs and program them themselves for other purposes.

Jensen had a meeting with a Stanford professor Andrew Ng, who explained to Jensen how he was using GPUs to process large data sets for machine learning. Ng discovered that what previously took him weeks using CPUs, could be done in days on GPUs.

This was the pivotal moment for NVIDIA where they decided to open up GPUs to be programmable to its developer community.

Creating CUDA unlocked two benefits:

Stop illicit use of its GPUS, and

Unlock the opportunity for programmers to use GPUs for all purposes

Here’s a link to the details of CUDA in case you’re interested.The rest is history.

NVIDIA was off to the races in the budding AI industry.

GPUs were installed in data centres.

AI started to come to life.

Slowing of Moore’s Law 💻

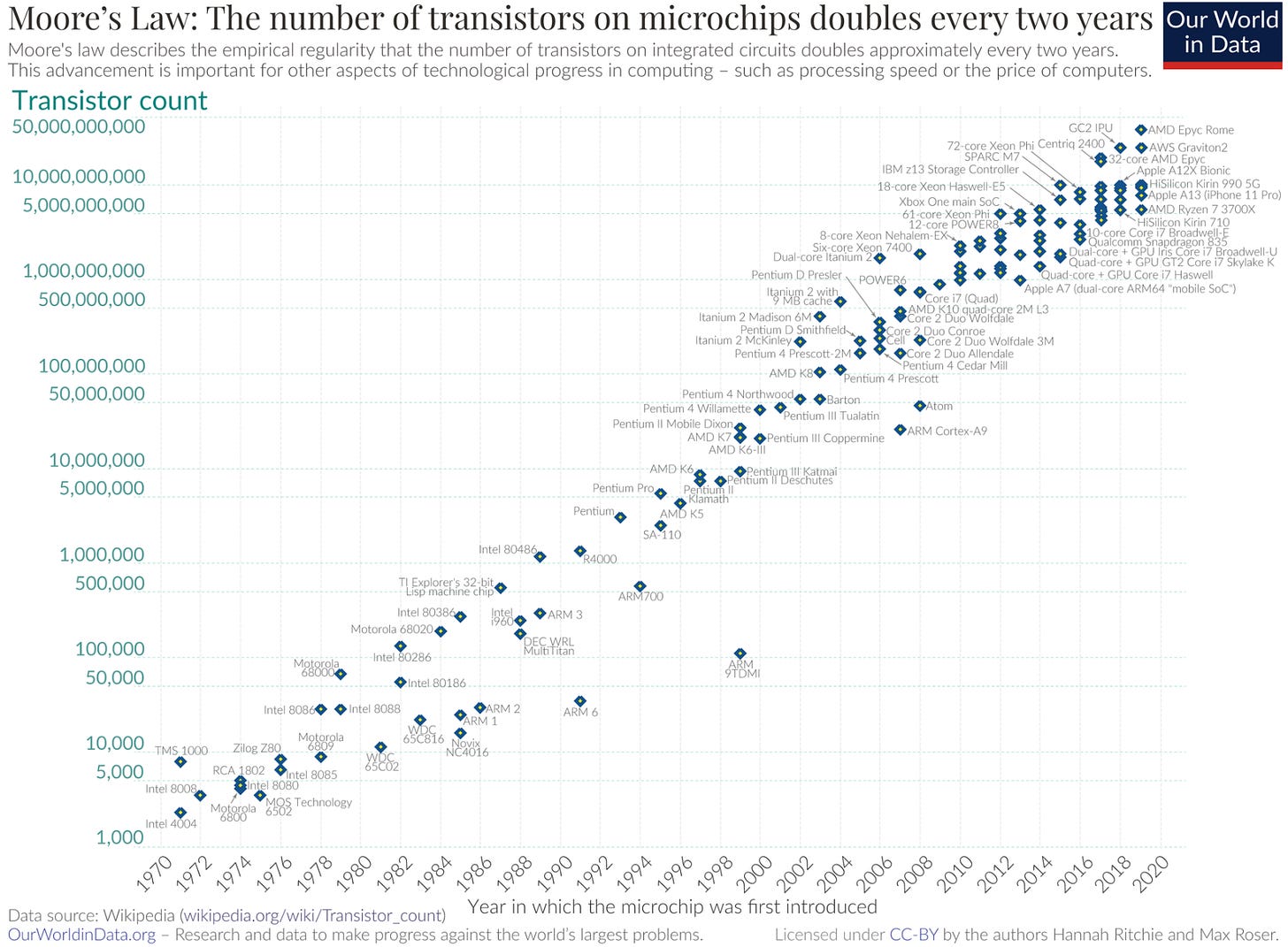

Moore’s Law was essentially the idea from the late Gordon Moore (founder of Intel) that the number of transistors on a microchip could double every two years. It was not a law as such - but more an aspiration for Intel at the time, to drive regular performance increases and push computing forward.

And that they did!

But it’s no question that keeping up with Moore’s Law has become difficult in the past 5 years. Performance increases have become harder to achieve at the chip level. Therefore the HPC (high performance computing) industry has to find new and inventive ways to improve computing performance.

Here are a couple of ways that have been thought of (which I won’t go into here):

Advanced Packaging

Chip-level connectors

Semiconductor differentiation - i.e. companies like Google designing proprietary chips to manage their specific workloads efficiently - rather than using a general-purpose Intel CPU which might have poor performance for Google-specific workloads.

The way forward that NVIDIA decided was big and ambitious…

The Data Centre is the New Chip

Fabricated Knowledge, a Substack page dedicated to semiconductors, made the point that if you squint at a a picture of a data centre, it kind-of looks like a chip.

The slowing of Moore’s Law meant that performance gains at the chip level would be hard to get. But there was still plenty of hardware that could get optimised at the data centre level.

The insight was to focus on the connectors between data centres - scaling computing that way.

If you’re into the details and implications of this - I would highly recommend the Fabricated Knowledge article below (paywalled).

In any event, that’s where NVIDIA decided to go. They would focus on optimising the wires that connected GPUs and data centres together.

Which is FINALLY…

FINALLY…

FINALLY!

where we start to explore Mellanox.

Mellanox 📶

Mellanox was founded in Israel in 1999 with a focus on high-performance networking. Their initial technology focus was something called “Infiniband” - which we’ll touch on soon. The company IPO’d in 2007, with a market cap of $500M at the time. Around this time they started to work on another technology called “Ethernet” - which more people have heard of, and definitely a greater number of firms worked on.

Long story short, through a series of R&D investments and acquisitions, they positioned themselves as key suppliers to data centres, HPC, and most recently AI acceleration.

Mellanox became a key supplier of NVIDIA, selling them a wide portfolio of networking technologies - Infiniband being the main one. The two companies, therefore, had collaborated to some extent for years before NVIDIA made the offer to acquire them.

Why Acquire Mellanox?

There were probably three main reasons why NVIDIA had Mellanox on the radar at the time:

Tighter integration and collaboration around AI

Fending off competitors

Infiniband vs. Ethernet at the time

I’ll expand on each of these.

Side note: This is not a technical blog - and nor am I a technical person - so I’ll keep the discussion around Ethernet and Infiniband simple. Tighter integration and collaboration around AI

As mentioned earlier, NVIDIA had been working with Mellanox for years and collaborating on R&D going into data centres.

As mentioned earlier, Jensen Huang saw that AI acceleration relied upon faster, scaled computing. The way to make quick efficiency gains was at the data centre level, and no longer at the chip level. Acquiring Mellanox was a 1+1 = 11 moment to capture valuable R&D resources towards this vision of AI.

Fending off competitors

It’s possible that another reason for buying Mellanox was shutting off competitors.

Mellanox was the dominant supplier of Infiniband - and probably invested the most R&D dollars in the industry. If one of NVIDIA’s competitors or frenemies were to buy Mellanox, they’d have to pay a toll to access Infiniband technologies, or have Infiniband bundled with other technologies that NVIDIA would be “forced” to purchase. This could potentially reduce the system-wide performance of NVIDIA’s chips when plugged into a data centre.

Here’s a few competitors that were apparently looking at acquiring Mellanox:

Marvell had shown interest for years prior to 2019.

Xilinx was rumoured to have shown interest.

Microsoft too…

Intel eventually engaged in a bidding war to buy Mellanox - however their last price was between $5.5-$6B - vs. the $6.9B that NVIDIA ended up paying.

Infiniband vs. Ethernet

From what I understand, it’s not that NVIDIA was hitched to Infiniband technology by buying it. They still used Ethernet. However, purchasing Mellanox gave them access to Infiniband that might have been shut off by competitors. At the time of acquisition they both had different pluses and minuses.

Ethernet

Ethernet had a much broader ecosystem than Infiniband - with many competitors and suppliers. One company did not own the technology. Therefore there was no chance of a single company blackmailing the data centre ecosystem. It was also developing very fast.

In 2019, however, it had a performance gap vs. Infiniband in terms of latency (and apparently also bandwidth at the time).

Infiniband

Tail latency advantage vs. Ethernet was important for NVIDIA at the time of acquisition.

Here’s a list of applications that require low tail latency - just to give you a picture of why it’s important. Some of them don’t apply to data centres - but you get the point:

Autonomous Vehicles and Robotics

Ultra-low latency is required for real-time decision making while a car is driving itself. Millisecond delays can create problems with obstacle avoidance.

Industrial Automation and Control Systems

Active monitoring and fault detection in factories and energy grids requires very low latency.

Multiplayer Online Gaming and VR

This one is obvious. Low latency improves game play, and also stops people from having motion sickness when using VR goggles.

So there we have it. NVIDIA’s acquisition of Mellanox gave them unchecked access to Infiniband and tighter integration. In addition, the tail latency advantage of the technology gave them a leg up in the AI acceleration vision that they had seen coming.

How has Mellanox Performed? 📈

NVIDIA’s CFO talked about the pro-forma financials of Mellanox at the time of acquisition:

For those less familiar with the company, Mellanox generated approximately $1.1 billion in revenue in calendar 2018, up 26% from the prior year. Calendar 2018 GAAP gross margin was 64.3% and non-GAAP gross margin was 69.2%. GAAP operating income was $112 million and non-GAAP operating income was $270 million.

In late 2022, Chat GPT launched, showcasing the potential of LLMs. Thereafter, NVIDIA revenues and profits EXPLODED as the investment gold rush into AI began. Companies were valued based on how many GPUs they had from NVIDIA. And talented AI engineers would only move to another company if that company could guarantee their GPU supply:

No hardware = No cool AI stuff to build

The US government even joined the gold rush, with the Senate recommending a non-defence AI investment package of $32B. There were also other Federal packages announced to explore the technology.

All of this has resulted in NVIDIA’s revenues and profits exploding over the past 5 years since the acquisition of Mellanox. After all, when a company says they’re investing in “AI”, they’re very often either hiring people or writing a blank cheque to NVIDIA.

NVIDIA began to disclose their Networking Revenue - the segment to which Mellanox belongs.

Networking Revenue was $3.2B in the quarter alone!

Annualising at this rate (which would probably be under-selling the actual result) would mean revenues of $12.2B for the year. I would guess that profits would have gone up at a faster rate, given the operating leverage in manufacturing and tighter integration of R&D.

If we assume a doubling of margins this would mean around $2.5B of profit for the year.

This investment has been a massive home-run.

But if we look at the 5 year stock chart again - would it have been a better use of NVIDIA’s cash simply to buy back their own stock in 2019, rather than buying Mellanox for $6.9B?

It’s really quite hard to say.

On the one hand, NVIDIA would have done well without Mellanox - even if owned by a competitor. Maybe NVIDIA would have faced higher prices for Infiniband, or had less integration with the technology. But NVIDIA’s overall advantage in AI was so great that they would have done well regardless.

On the other hand, it’s clear that acquiring Mellanox allowed NVIDIA to move faster with performance increases and AI compute scaling. So they may not have reached as high a current market cap without Mellanox in the portfolio.

In any case, we can only live life looking forward.

It’s clear, however, that Mellanox was at least a hedge against losing VIP access to Infiniband. And that alone made it worthwhile as opposed to a share repurchase.

The Future of Mellanox and Infiniband

The half-life of high tech businesses is not long. There might be a situation in 5 years where NVIDIA needs to reinvent their business model to avoid erosion of competitive advantage - or simply to stay relevant.

Contrast this to Berkshire’s investment in the Burlington Northern railroad, which can be expected to still be operating in a similar way 100 years from now.

At the time of writing, Ethernet has caught up to Infiniband on every front (speed, bandwidth and latency). If NVIDIA had taken sides on a particular networking technology this could have been detrimental to them.

High tech is a really tough game - and there are no sacred cows.

For those brave souls who want to go into details, check out this post from Fabricated Knowledge:

Though Infiniband and Mellanox still have growth to die for, NVIDIA has developed its Ethernet platform “Spectrum-X” alongside.

NVIDIA was never wedded to one technology, and that Mellanox was an acquisition to keep networking options open and away from the hands of competitors.

What kind of acquisition was this in the end?

This is an interesting place to discuss capital allocation in high tech. As mentioned above, this acquisition almost looked more defensive than offensive. Keeping a technology open rather than letting a competitor snap it up and thereafter determine standards on how the tech was used. It was part financial, part deterrence.

It also opens up the discussion of how much capital NVIDIA really needs to invest back into the business to keep the core business margins high. NVIDIA is gushing cash now, and probably will as long as the current AI Capex boom continues. But it will have to keep investing big sums to keep its advantage and keep invaders away.

In summary, it’s not like a Moody’s which requires zero ongoing investment to run the business. And it’s not like the old advertising agency roll-ups which I described in my previous post 👇

- where they could use all cash for buybacks in the early 1970s.

Future Capital Allocation and Margins 🤑

There was a really great Invest Like the Best Podcast where the anonymous guest said that every person was looking at NVIDIA’s yearly operating profit and starting to attack it. Capitalism would almost ensure NVIDIA’s demise unless they stay miles ahead.

Looking at the semiconductor value chain, it’s clear that NVIDIA might have (accidentally) taken it too far in terms of value capture. They rely almost 100% for supply from TSMC. The CEO of TSMC had this to say about NVIDIA:

'I think those products are really valuable...but I am thinking about showing our value as well'

TSMC lets customers earn healthy profits - a clear commitment to sharing value with the entire ecosystem and not giving too many incentives for customers to invest in a second source manufacturer.

Go one level down and ASML, a monopoly supplier of EUV equipment, states a similar philosophy of taking 50% of the profit for itself, and then giving 50% of the profits back to the customer. It’s like one big happy family.

It could well be that NVIDIA will have to pay up as TSMC raises prices soon - and the current profits we see are above normal. In isolation, this could depress margins.

But what has been NVIDIA’s response?

NVIDIA as VC 💰💰💰

One of the biggest VCs in Generative AI early stage companies has been NVIDIA.

NVIDIA seems to be migrating up the value chain - having previously only dabbled in hardware. Now with cash gushing out of the business, it makes sense to capture part of the economics downstream. I’d recommend reading the above substack post for more detail. But here’s some of the deals the’ve recently been involved in (from the above article):

AI21Labs, alongside Google

Runway, together with Salesforce and Google

Cohere, by participating in its US$270 million Series C in June

Inflection, alongside Microsoft and Google

Adept, alongside Microsoft

Mistral, by participating in its EUR450M funding round in December

In addition, they’ve also invested in a $73.6M round in Perplexity, a product that I really love and use for more than 90% of my searches now.

I personally love these moves. They offer a hedge against NVIDIA margin capture from other participants in the value chain. In addition, they offer tighter integration and real understanding of the end user of AI, increasing NVIDIA’s ability to work backwards and make hardware investments with a tighter feedback loop around customer needs.

NVIDIA’s Investment Style 💸

Overall, Mellanox and the VC investments show NVIDIA’s strategy to invest to preserve optionality, as well as hedge their core business.

I’d rate their investing prowess a 10/10, given that they regularly have to bet the farm and go all in. It’s not easy to do what NVIDIA has done through the years.

The industry makes a difference. Moving fast is a must, and a lower half-life of investment is par for the course in technology.

“You want to position yourself near the tree. Even if you don't catch the apple before it hits the ground, so long as you're the first one to pick it up." - Jensen Huang, CEO of NVIDIA

NVIDIA is not Moody’s or Berkshire Hathaway, where we can expect the core business will be there 50 years from now.

No, NVIDIA has to keep investing and pivoting to stay alive.